We Are America

Rose Colored Glasses

By Dominique

North Quincy High School, Massachusetts

The very first book I read by myself was The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter by Arielle North Olson. Tucked between my mom’s arms and covered by the seemingly enormous picture book, I slowly traced my chubby fingers over the sentences. Flipping through all the pages on my own, I learned about a young girl who successfully guided ships during a storm when her father was unable to do so himself. It was a monumental achievement that my mother wanted to celebrate, but I was more focused on finding another book to read afterwards. While this was the beginning of my never-ending hunger for reading, it was also the first of my female role models. Growing up around strong women who are passionate about STEM, all the books I devoured featured female scientists, engineers, and mathematicians. I learned about intriguing inventions, achievements, and discoveries by women of all cultures, races, identities, and backgrounds. Marie Curie glanced over my shoulder when I read about her discoveries, and Ada Lovelace introduced me to the world of computer science.

It was natural for me to develop a mentality where women comprised the majority of the STEM field. While all of these women had obstacles, such as barriers to enter the field or technical setbacks, I took them as signs of the past or inspiration to work harder.

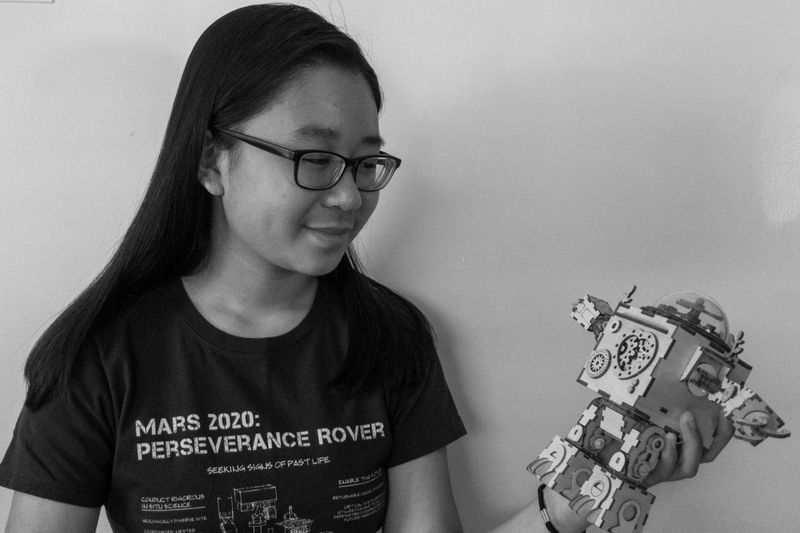

I kept this mindset for many years, never acknowledging the signs even when they were right in front of me. When I entered my first robotics meeting in sixth grade, I was one of three girls out of twenty. When I attended my first build-fest at the Cambridge Science Festival, I was the only girl who wanted to design a 3D model. Although I was too focused on learning or building at these events to notice the gender imbalance, I finally realized something was unusual a few years later.

My mom and I had the opportunity to attend a lecture about the first black hole photograph with guest speaker Katie Bouman, one of the lead scientists. Enthusiastically rushing my mother into the hall, I sprinted to the front row and sat on the edge of my seat for the entire presentation. Watching the panel, which was filled with a star-studded cast of scientists, was one of the best experiences in my life. However, when I looked back at the photos I took, I noticed there were only two women out of the fifteen panelists.

After all those events and a few more robotics competitions, programming events, engineering lectures, my rose-colored glasses disintegrated. I began reading articles, newspapers, and papers about the gender gap that divides the STEM field. I learned how women make up 30% of the STEM workforce according to the 2019 US Census; and while this number has risen since the 1900s, it is still a startlingly small percent.

It only takes one event to show the gender difference, but there are countless that aim to solve it. From Women's Marches across the nation to the rise of social media posts, awareness of this crucial issue has risen dramatically in the last few years. With announcements of the first woman to the Moon and the first Nobel Prize awarded to two women, barriers have been broken and opened for future generations. I wanted to help as well. I began attending events for young girls interested in engineering and took efforts to meet new female role models, friends, and mentors. At these events, we collaborate to program websites, host meetings, and teach others about women in STEM. With the stories of Marie Curie, Ada Lovelace, Katie Bouman, and a growing network of young females, I hope more girls will be fascinated with STEM as much as I was and still am. In the meantime, I’m excited to continue advocating for women in STEM and exploring this wonderful field.

© Dominique. All rights reserved. If you are interested in quoting this story, contact the national team and we can put you in touch with the author’s teacher.