We Are America

Through the Fire and Flames

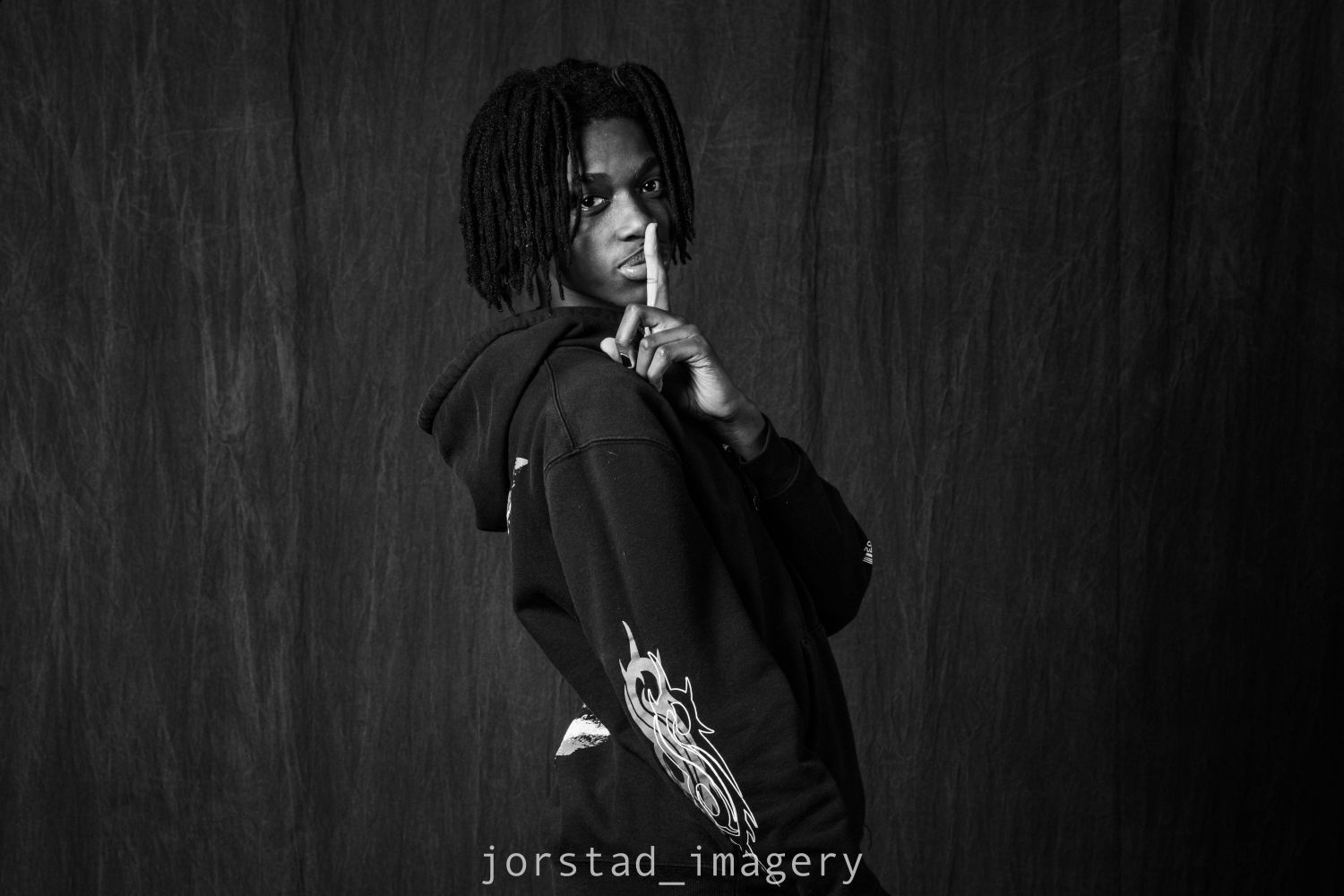

By Kembo

Irondequoit High School, Rochester, New York

When I arrived in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in the city of Kinshasa in Africa, I disembarked the plane and immediately saw how different it was. In America, in most places, when you get off the plane you walk through a bridge that connects the airplane to the airport. In Africa it is different. There is a set of stairs that connects from the outside of the airplane right onto the ground. The next change I noticed was being in a place where everyone speaks my native language, Lingala. The only people I know that speak it here in America are my family members. We got through to luggage pick up, and we were greeted by hundreds of people also getting their luggage, but more importantly, our Uncle Patrick, my dad’s brother, who would be the one driving us around Kinshasa. Having finally found our luggage, we made our way out of the airport. Outside it was dark but not cold. I noticed billboards in my language, which was a new sight, but the overwhelming detail that I noticed was the sheer mass of people. The airport in Kinshasa was almost like a balloon filled with air, ready to explode. The amount of people there was double, if not triple, the amount in the Rochester airport back home.

Once we arrived at our hotel, which is called Fleuve Congo and translates to the River of Congo, we entered to discover a luxurious, 5-Star hotel. Our room was lovely and had a stunning view. As it turned out, this hotel did not accurately predict what the rest of our trip would look like in the coming weeks. For the first week in the city of Kinshasa, we found it very different than in America: overcrowding, run-down homes, and many motorcycles. There were people selling miscellaneous items, like dogs, on the side of the road. You definitely would not see something like that in the U.S.A.. The most memorable part about the trip was when we went to the second city, Lubumbashi. We walked to my mother’s school, to my dad’s school, to my dad’s house, then to my mother’s house. The walk took forever. At every step I took, I hoped it was over. It was very hot, my feet started to hurt, and I was thirsty. On the walk, there were hundreds of people also walking, due to the population. There were street vendors and other small shops that my parents would point out. They would also recount memories they had at certain locations around the area, even pointing out the hospital where my brother was born. It was cool to hear the stories of their life before me, even on that treacherous walk. The distance that my parents had to walk just for their education is not something we Americans have to endure. They don’t have separate districts spaced fifteen minutes apart; they didn’t have the luxury of cars and rides. The walk from my mother’s school to her home was at least an hour. I sympathized with them and all they had to go through for something as little as going to school, something I take for granted in America. Our experience in Lubumbashi also made me thankful for their journey. Here in America, I have the privilege of living five minutes away from my school. The journey my parents traveled is one I never have to face, thanks to their sacrifices for the journey they took from Africa, at the age of 18, to travel all the way to the United States. It was all to provide a better life for me and my entire family. That trip to Africa changed my perspective and makes me grateful that my parents took that first journey, and for the way my life is, due to my wonderful parents. It couldn’t be any better.

© Kembo. All rights reserved. If you are interested in quoting this story, contact the national team and we can put you in touch with the author’s teacher.